Could AI kill the soul hypothesis?

Karl Popper made a big stink about falsifiability. If you’re making a statement about the real world, there had better be some way to disprove (falsify) your statement. Let’s say your statement is “It’s raining”. I should be able to open my window and stick my arm outside and see if it gets wet. Writing as a software developer, I might use the shorter word “testable”. If your assertion is testable, it may be right or it may be wrong. I and others are empowered to figure that out.

If the assertion is that life continues after death, how does one render that assertion testable? We must say more. “Ghosts exist”, for example, is testable, as long as your definition of “ghost” includes that they have some observable impacts on the living world. It should be possible to take a picture of a ghost, record a ghost saying something or moving an object. People make ghost hunter TV shows, of course, but the wider scientific community remains unconvinced because this “evidence” doesn’t meet the high standards of that community. One must rule out trickery, and con men are clever, while people are easily fooled and often want desperately to believe.

As science slowly pushes back the boundaries of our ignorance, in fits and starts and with many missteps, it leaves us with a shrinking “God of the gaps”. People ascribe to God that which is not well-understood. If one prays for rain and it does rain, is that because God answered the prayer? Or is that because of atmospheric conditions, and the prayer had no real impact on the outcome? Which answer you give is highly dependent on whether you live in 2025, or in 1525. Now, the weather is a chaotic system, which means it may be impossible, or highly impractical, to expect to predict it with absolute accuracy. Does that leave us still invoking God as the decider between “it rains now” and “the rain holds off for another five minutes”? Or do we stop invoking the God hypothesis entirely?

Although the God hypothesis is losing ground to atheism in the physical world these days, it still plays a big part in describing the afterlife. The next realm is supposed to be unknowable, a space still left to God's judgment, because folks who die cannot return to tell us about it (usually). Religion tells us what to expect after death, and in most religions, what we do in this life is the most important determinant in what sort of afterlife we expect. If we’re good, we go to heaven. If not, we go to hell. These two experiences are so different that it becomes critical to live one’s life according to religion’s dictates. The trouble is that religion’s assertions are not testable.

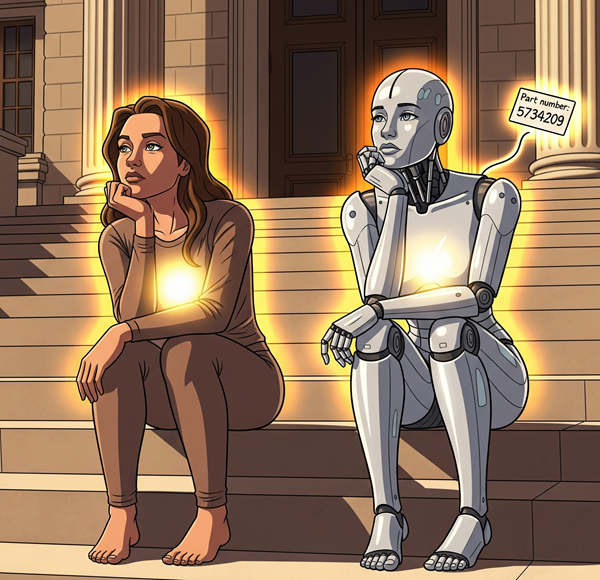

The part of us that continues on, after the body dies, is called the soul. Indeed, if people have souls, then people are souls. The bodies are just puppets that the souls maneuver around, discarded at death. Since souls are immortal, and are the seat of our conscious experience (so the story goes), they’re much more important than bodies. We care about what happens to souls because it’s our ultimate fate, and we fear being tortured eternally in hell.

It’s essential that the soul has an important part to play in decision-making during life. Imagine if this were not true, if the soul were a passive passenger in the body, while the body and the brain made all the decisions throughout a life of 80 years or more. The body and brain decide whether to sin, and the soul has no say. Why, then, is it the soul that suffers the consequences, the eternal punishment for that sin, after death? This offends our sense of justice. If there is a soul, it must be capable of making life decisions or at least influencing them.

As we learn more about the brain and neurochemistry, about neurotransmitters and how they impact our thinking, there is less room for the soul to make decisions, just as there is less room for God to decide whether it rains. We have a “soul of the gaps”. So far, though, for most people the soul hypothesis is still hanging on.

Now we have a new technological twist. A host of big corporations claim they’re on the verge of developing Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). There isn’t a nice, clear definition of AGI, but the rough-and-ready definition is “a machine capable of making decisions as effectively as an average human, in all the wide contexts of human life”. If you can imagine hiring a human to do a job, whether that’s as a secretary or a soldier or a surgeon or a CEO, then an AGI ought to be equally capable of doing this job, well enough that you’d consider hiring the AGI alongside qualified human applicants. (This is not about whether you should use an AGI to replace a human job. It’s about whether you could, without harming your business.)

If these corporations should succeed in convincing us that they’ve built an AGI capable of human-level decision-making, then the soul hypothesis will face a new problem. We will share Earth with examples of machines we have built out of metal and silicon, doing what we do, as well as we can do it, with no soul component installed by the manufacturer. If they can do all that decision-making without a soul, does that suggest we don’t have them, either? Perhaps the soul hypothesis is, in a sense, testable after all.

Comments

Post a Comment