Response to "ChatGPT can never replace programmers"

chatGPT can never replace programmers

"Never" is a long time.

In a narrow sense, yes: maybe you can say that ChatGPT will never replace programmers entirely. But that's a straw man. We don't really care about the narrow statement, do we? Even if you expand it to "Large Language Models will never replace programmers entirely" (and I grok the argument that they can only ever mimic human-produced writing), that's not what we care about, either. What keeps us up at night is this: Can we never build any machine that can think well enough to replace programmers?

There's no way to avoid the philosophical, with questions like this, so let's not mince words or dodge the key issue. Is there a magical component to the human brain?

You, reader, can believe what you like. I can only describe my own beliefs: I'm a physicalist. I believe that matter and energy exist, the stuff that physics tries to study and understand... and that's it.

If you believe there's something that's impossible to study with the tools of science, and that something somehow drives our thought processes, then, sure. An inevitable conclusion is that we'll never be able to replicate that, because we can't study it, we can't build it. We can't even touch it. It's part of us, yet beyond us. Somehow.

I see no evidence of this. Or rather, I see plenty of evidence, occurrences that people point to as evidence, but it's all bad evidence. The more we learn about our own brains, the more we realize that they're the product of evolution, and having evolved by chance, they take all kinds of crazy shortcuts. Those shortcuts result in built-in biases, like the tendency to invent explanations for actually-random occurrences and then believe in those ideas with insufficient proof. When the scientific method is rigorously applied to this supposed evidence, the anecdotes turn out not to be repeatable.

Our brains are control systems and predictive engines, built of neurons. They accept electrical signals as inputs. Neurons form connections to each other, that may be of various strengths, and may be positive (reinforcing) or negative (inhibiting). These connections are adjusted based on feedback: did the predictions prove to be right, or wrong?

A neurologist will tell you I'm way oversimplifying, and that's fine -- it's not my field. But that oversimplified understanding was enough to give us machine learning technology. ML systems can do things like recognize the handwriting on checks. That's something no programmer knows how to do. Go on, show me the algorithm for recognizing handwriting on a check. Give that problem in a hiring interview. Show me the algorithm for doing what ChatGPT does: scanning the entire Internet, and writing something similar to what others have written... but not the same.

Peer inside an ML system, examine the specific weights of the connections, and you won't gain a better understanding. The same can be said for trying to understand how software developers do what they do, by opening up their heads and examining the specific wirings of the neurons in there. It ain't an algorithm. As unsettling as it is, we have to accept that ML systems solve certain problems, which we can't solve ourselves by writing programs. This means that, in a sense, we don't truly understand the behavior of these machines we've built.

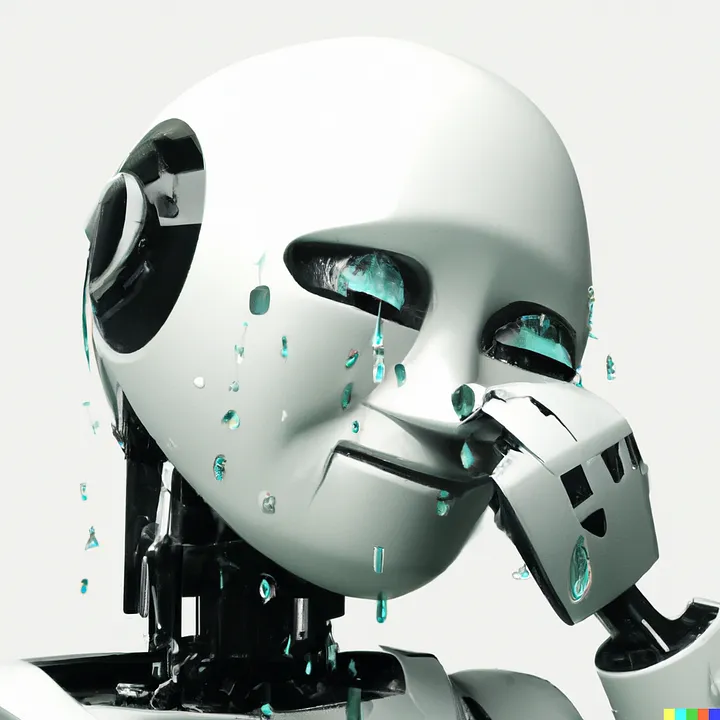

It's the resulting feeling, the sense that systems like ChatGPT are creepy, that inspires articles like this one. We rebel against the idea that machines might someday replace us, by saying "Yes but." The author doth protest too much. ChatGPT has limits, absolutely, but that's not the story. The headline is that ChatGPT can do more than most of us would have expected. It can't only write software (though imperfectly). It can answer questions about your taxes, or critique your writing, or help you compose better questions to ask ChatGPT. Its generality is startling, and we can assume that later versions will improve on it.

If ChatGPT is never able to solve all kinds of software development problems, that's only because the systems we have today are incomplete simulations of human brains. As a physicalist, I believe we'll continue to gain understanding of how our own brains work. There might be more going on than the interactions of neurons, but I believe it's all physical forces, quantum mechanics, atoms and molecules and cells and higher structures. What we're missing is either greater scale, or some other component of the brain that we've yet to pin down. That means -- unless human civilization ends first -- that it's just a matter of time.

Originally posted to Reddit

Comments

Post a Comment