Being Intelligent, Whatever That Means

This post was inspired by a talk called Being Human, given by Jason Wodicka, someone I worked with at Amazon.

This is a great talk, and you should watch it. Jason is a smart guy, and while he and I may not have arrived at exactly the same conclusions (or perhaps we "violently agree" and are just looking at similar ideas from different directions), I absolutely appreciate where he is coming from. What follows are my personal reactions and responses to the talk. Also I should note that this is hardly my first blog post on AI; if you'd like to read the others, see Never Is A Long Time and Buckle Up and... well, any of these.

Yes, Jason: You're quite right about the boom-and-bust, summer-and-winter cycle of AI. It's looked promising before, and we've been disappointed before. I, too, have been around for a while, and I too used to read Wired magazine in print. 😄 We must approach reputed AI developments with a big ol' grain of salt.

Turing's "imitation game" is at the heart of the philosophical question you've posed in this talk, a fun question explored by science fiction stories like Blade Runner / Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep. If a machine were ever to behave so like one of us that we couldn't tell the difference, would we deserve to give it fewer rights than we would give one of our own? Really, it's the same question explored in the idea of the philosophical zombie. If you're a solipsist, you can pretend you're the only one with conscious experience. Who can disabuse you of the notion?

Maybe ChatGPT can't fool us into thinking it has a mind. Have I managed to fool you into thinking that I have one?

I'm all on board that large language models have architectural limitations. An LLM per se is not likely to be capable of achieving AGI, not by simply making it bigger or feeding it more data. But to me, that's not the interesting question. It's a distraction. The more engaging question is whether we can build an AGI, and whether we will, and what might happen next. "When" would also be nice to know, but as you pointed out, there is still widespread disagreement on that. It's much too difficult to predict with any accuracy. To my mind, if it could be as soon as 50 years from now (and I believe it could), then we should be taking steps now to prepare for that.

I'm also well aware of the human tendency to anthropomorphize. I know ChatGPT is not conscious and not "really thinking". And of course your point about Eliza, and how people emotionally engage with it, is well taken: it says a lot more about us, about how we have evolved to be social creatures at all times, than it does about the machine. We are, frankly, bad at figuring out whether something has a mind. We're hard-wired to assume that nearly anything that moves is conscious, because conscious things are more likely to be dangerous, as tigers are. It's evolutionarily advantageous to assume so, until we become confident in our ability to predict the threatening object's behavior, and then to control it. Once we have control, we feel comfortable and safe and stop worrying so much. (Of course, this also leads us to objectify living creatures which is another problem.)

On the other hand, the ability of ChatGPT, Claude, etc. to solve real problems, to do useful work, is undeniable. They make mistakes -- but so do humans. Rather than this making me think LLMs are special, I'm more inclined to take the inverse course, and to posit that my own intelligence is not special.

This is in line with what we've learned time and again throughout history. We're not at the center of the solar system. We're not at the center of the universe (unless you consider every point "the center"). We're not fundamentally different from other apes -- we're just a tad smarter. We're not the only species on the planet that uses tools. And so on. We keep receiving lessons from the universe that humility is the proper stance.

We've done amazing things, discovering quantum mechanics and the age of the universe and the structure of our own DNA. If we can do them, a machine could do them.

So, sure, ChatGPT has been trained on how to be conversational. Well, so have I. So has everybody who has grown up as a human. In large part, we behave as we do because of socialization. Our experiences, interacting with other humans, have trained us how to respond in different situations.

When you say that "there are many people who believe that somehow... the model acquires a true understanding, but I can't count myself among them": Well no, me neither. Not ChatGPT specifically, nor Claude, nor any other currently available LLM. The bigger question is -- What is that, "true understanding"? We humans have some power of introspection. We can think about, and talk about, our own thought processes. So I can state that my mind holds a sort of model of the world, a model that includes modeling myself, a condition which I might term "self-consciousness". Does that definition of "self-consciousness" constitute "true understanding"? If an AI system could demonstrably do that, would it make a difference?

You also talk about the distinction between "deciding" and "choosing". There is subtlety here, too. We all have our preferences. But we do not choose our preferences. I can tell you I like chocolate ice cream. I cannot choose to prefer the taste of black licorice. What I'm saying is that I'm not a believer in free will. We may make choices, but ultimately, we are all a product of our genetics, the environment, and random chance. If humans have choices, then by any reasonable standard I can think of, machines can be built that are equally capable of making choices. Not the machines we have, but the machines we have yet to invent.

When you talk about how we're "getting close to the limitations of the goal" and it has "exposed the limitations of the goal", are those not the same limitations explored by Philip K. Dick? Maybe there is, in the end, no clear solution to the question of "how to determine whether this thing is a person". It may come down to a matter of opinion.

LLMs like ChatGPT have limitations that make their "thinking" distinctly un-human-like, in fact unlike any living creature's brain. The deficiency that stands out the most, to me (speaking as not-a-neuroscientist), is that they can't learn on-the-fly as we do, as animals do. If you carry on an extended conversation with an LLM, it will act as if it's learning, sort of, but that's just the conversational tool building up a bigger and bigger context window, enabling better predictions about what it ought to "say" next. If you open a fresh conversation, it starts over with its training data. And, what you say to ChatGPT has no impact on what ChatGPT says to me. It isn't influenced by what everyone is saying to it, unless OpenAI then takes those conversations and makes them, in turn, part of its next round of training data. Talking to it does not really teach it things in the moment.

But suppose that someone were to solve that. Imagine that the neural network could be recursive, or reentrant, or whatever the human brain is. I'm being vague here because again, I'm not a neuroscientist, but I do know that the strictly linear progression through layers employed by today's ML systems is unlike the human brain, whose network of neurons paint a far more tangled picture. What if the machine's neural network could be trained, its weights impacted, by every interaction with its inputs and outputs? What if it started out as blank as a human brain's, with a physical presence (or simulation of one) and some senses and power to act? What if, like a living creature, it had certain built-in preferences such as to avoid pain (a quantifiable negative signal of some sort), and to seek approval and praise, and was rewarded (and strengthened the relevant pathways) whenever it correctly selected the right responses leading to a good outcome or avoiding a bad one?

I'm not all that interested in whether an LLM, as they exist now, could someday be an AGI; I don't think that will happen. There are cliffs here that cannot be surmounted merely by "scaling up". Rather, I'm interested in whether the next breakthrough in neural net architecture is going to be the one that seriously blurs the line between our creations and ourselves. Given how much money is being poured into this research now, in part by obsessive people richer than have ever before existed, there's a chance we have seen the last AI winter. We might keep pouring on the research funds until we reach AGI, whether that's five years from now or fifty.

And as Nick Bostrom pointed out in his book Superintelligence (which I highly recommend, though it is -- as Tim Urban pointed out -- somehow simultaneously terrifying and sleep-inducing), machine personhood may not be the point. An AGI may have no self-consciousness, yet have tremendous power to change the world. This power could easily fall into the wrong hands, if indeed any human hands could be said to be the right ones.

You say that we're being asked to worry about the "hypothetical" risks of AGI, instead of "the threats that we can already see". This is, to me, a false dichotomy. I believe we should worry about all the threats to our continued existence and progress: climate change, demagoguery, pandemics, disinformation, religious fanaticism, asteroid strikes, and AGI and everything else. As a species, we've demonstrated repeatedly that we're pretty bad at responding to existential threats, like climate change, even after accumulating a mountain of evidence that real damage is already taking place. We have massive wildfires in California, concurrent with an administration that wants to "drill, baby, drill". We didn't evolve to respond to catastrophes that unfold over generations. We also didn't evolve to respond to catastrophes that are anywhere between 5 and 90 years away. But we need to be better at both. If we should wait until something exists that we can all agree constitutes AGI or ASI, well that's too darn late.

I suspect we're just not built to be able to consider this whole question of AGI's feasibility rationally, at all. There is a dangerous tendency to anthropomorphize tools like ChatGPT, and imagine them to be smarter than they are, and to be conscious or have feelings. There is an inverse danger, of being unwilling to appreciate the potential of machine intelligence. The temptation to anthropomorphize is linked to our tendency to be fearful and cautious, even paranoid, a tendency partly responsible for keeping our species alive, but that can lead us into error and overcorrection. The temptation to dismiss the danger is also emotional. We fare better when we are optimistic rather than pessimistic, and so, we want to believe that everything will be OK: tomorrow, and next week, and next year, and for the next generation. This lets us ignore the slow-moving existential threats. We also have multiple such threats to deal with, as you noted, and so there is further temptation to set some of them aside entirely.

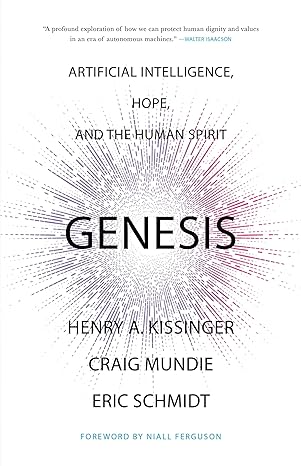

If you choose to believe the chance of developing AGI is zero percent, well, that is your prerogative, but it's not where I stand. If you believe the chance of developing AGI is instead 0.5%, then... great! I can roll with that. And a 0.5% chance is much too high for us to not be thinking about the possible consequences. If you're able to admit of a 0.5% chance, then I highly recommend Henry Kissinger's book Genesis (co-authored with Craig Mundie and Eric Schmidt). He thought it a serious enough concern to be his life's final work.

Comments

Post a Comment